THE HISTORY OF P.T.S.D.: 5,000 B.C. TO AFGHANISTAN

- jim63322

- Oct 4, 2024

- 85 min read

B.C.

India (5,000 B.C.)

India (5,000 B.C.) Samba dressed as a pregnant woman, presented to the sages - Illustrations from the Barddhaman edition of Mahabharata.

In Western literature, the oldest description of symptoms of PTSD, an anxiety group of disorder, is seen in Homer’s Iliad, written around 720 BC. According to Shay, Achilles was suffering from symptoms of PTSD. However, in the Indian literature, it was mentioned around 5000 BC.

The Mahabharata is a compilation of Indian epics describing symptoms similar to soldiers fighting wars almost 5,000 years ago. Stories from the Buddhist Jakarta record the story of a monk suffering frightful mental images and emotional numbing.

Assyria (3200 B.C.)

The Assyrians left very detailed accounts of their military conquests and battles, according to 2015 study.

Some of these texts were medical texts, which document the traumata and injuries that Assyrian soldiers suffered during these campaigns even though they were protected by various forms of shields, helmets, and armor made from iron scales, a technology that reached its highest level of effectiveness in the Assyrian period. Unfortunately, offensive weapons had also reached their highest level of effectiveness in that period.

Mark Miller has written about the earliest records that address combat trauma dating to ca. 3200 B.C. (“Weapons and tactics change, but P.T.S.D. goes back millennia”). In ancient Uruk (Iraq), the Assyrians were the first to make cuneiform impressions of their military campaigns and battles. I will give a small sampling of what archaeologists discovered among the 500,000

Middle Assyrian Cuneiform tablet. administrative memorandum.

“If his words are unintelligible for three days [...] his mouth [F...] and he experiences wandering about for three days in a row F...1.”

“He experiences wandering about (for three) consecutive (days)”; this means: “he experiences alteration of mentation (for three) consecutive (days).”

“If his words are unintelligible and depression keeps falling on him at regular intervals (and he has been sick) for three days F...]”

Assyria (3200 B.C.)

Audience scene with procession of horses, soldiers, chariots, dignitaries and eunuchs (section). Wall painting from the Neo Assyrian palace at Tell Ahmar, ancient Til-Barsip (or Kar-Salmanazar), room XXIV, VIII century BC. 1/1 scale facsimile by Lucien Cavro, reproduced at the Louvre Museum.

Another Assyrian warrior received a diagnosis from an ašipu (ashipu) “doctor” recorded on clay tablets:

“in the evening, he sees either a living person or a dead person or someone known to him or someone not known to him or anybody or anything and becomes afraid; he turns around but, like one who has [been hexed with?] rancid oil, his mouth is seized so that he is unable to cry out to one who sleeps next to him, ‘hand’ of ghost (var. hand of [...]).”

“[If ] his mentation is altered so that he is not in full possession of his faculties, ‘hand’ of a roving ghost; he will die.”24

“ . . . but, like one who has [been hexed with?] rancid oil, his mouth is seized so that he is unable to cry out to one who sleeps next to him, ‘hand’ of ghost (var. hand of […]).”

Egypt (1900 B.C.)

Drs. Sethanne Howard and Mark W. Crandall have described an Egyptian physician around 1900 B.C. who had quite a visceral reaction to his trauma. Hori wrote, “You determine to go forward. . . . Shuddering seizes you, the hair on your head stands on end, your soul lies in your hand.” PTSD? Something happened to cause him to feel as he did.

Egypt (1900 B.C.) Warriors figures ushabtis.

Greece

Homer (850 B.C.) )

In book XXIV of Homer’s Iliad, written about 850 B.C., Achilles becomes prey to recollections about his friend Patroclus, who is killed in combat (book XVI). These recollections are recurrent and. cause very disturbed sleep (Homer, 1950):

“But Achilles went on grieving for his friend, whom he could not banish from his mind, and all-conquering sleep refused to visit him. He tossed to one side and the other, thinking always of his loss, of Patroclus’ manliness and spirit... of fights with the enemy and adventures on unfriendly seas. As memories crowded in on him, the warm tears poured down his cheeks.”

Greece 850 B.C. The Illiad of Homer.

Hippocrates (460–370 B.C.)

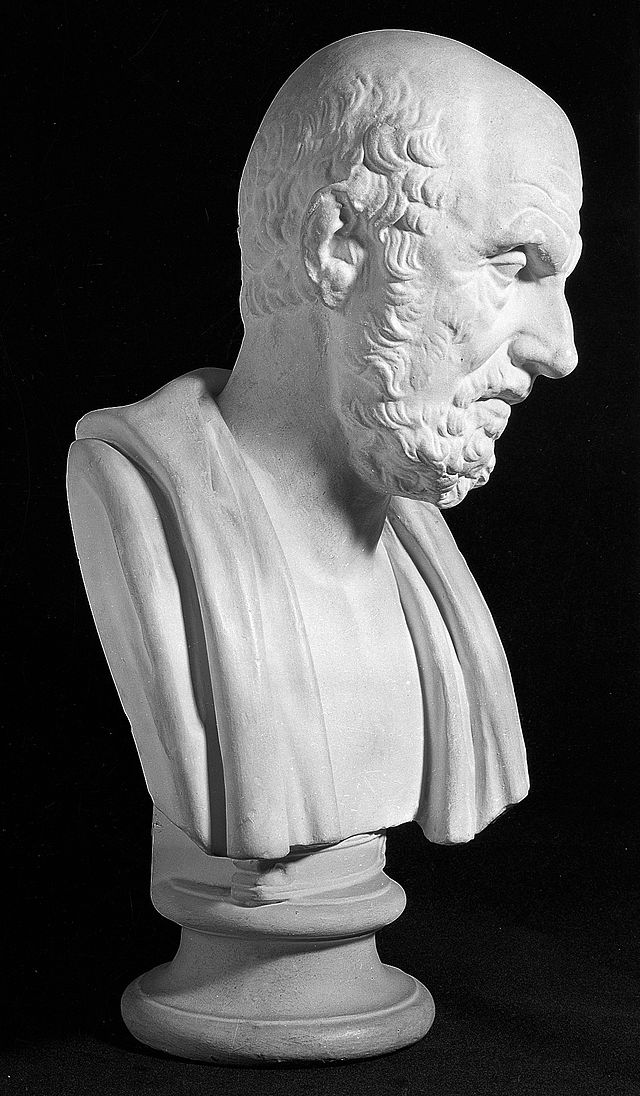

Hippocrates describes two female patients who displayed symptoms of PTSD. He noted the first woman’s fear, depression, and incoherent speech. The second woman was mute, fumbling, plucking, and scratching. She pulled her hair out, laughed, and wept, all without speaking. At the battle of Marathon in 490 B.C., we discover Epizelus, an Athenian soldier and the son of Cuphagoras.

Facsimile of a bust of Hippocrates.

In battle, Herodotus recorded this fearless warrior was struck with total blindness, which lasted the remainder of his life. Epizelus believed he saw a giant, bearded warrior who, instead of killing him, slew the man next to Epizelus. PTSD? In his research spanning the centuries from Thermopylae to Hue and the Tet Offensive of 1968, Stephen Bentley tells us that soldiers have always had a disturbing reaction to combat.

Alexander the Great (356–323 B.C.)

Plutarch recorded in his The Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans at 22, 2 years after his father was assassinated in 336 B.C., Alexander crossed the Hellespont with an army of just over 30,000 men to conquer the “known” world. In 10 years of bloody hand-to-hand combat, in which he received several near-fatal wounds and saw legions of comrades struck down by injury and disease, Alexander subjugated the vast Persian Empire of Darius III to become “Lord of Asia.” However, when he reached western India, his exhausted troops refused to march further, forcing him to halt his conquest to the east and return to his new capital at Babylon. Although until that time, he had been a peerless leader, brave, adventurous, adaptable, ingenious, and considerate of those who served under him, Alexander began to exhibit disturbing changes in his character during his return from India. First, he drove his exhausted army through the Gadrosian Desert, where two-thirds perished from dehydration, starvation, and hyperthermia. Then, he began executing the lieutenants and satraps who had served him as middle managers of the empire during his conquests to the east. By the time he reached Babylon, he was drinking heavily. He had become so pathologically suspicious and easily alarmed that he regarded the “least unusual or extraordinary thing as a prodigy or a presage.” During one of his alcoholic binges, he developed a mysterious febrile illness that killed him and ended plans then formulated for renewed conquest around the Arabian peninsula and across North Africa.

Alexander the Great mosaic.in the British Museum.

E. Badian, in his book Studies in Greek and Roman History, found that Alexander lost interest in things he used to enjoy. He felt distant and cut off from people. Falling or staying asleep, irritability, or angry outbursts troubled him. In Alexander’s case, because of his nearly constant drunkenness for at least seven months before he died, alcohol dependence rather than P.T.S.D. has to be considered the principal diagnosis. It is also possible that after more than a decade of fighting, scheming, and murdering in pursuit of absolute power, Alexander changed because he realized that absolute power demanded eternal vigilance.

Appian (149 B.C.)

Appian describes the sack of Carthage (149 B.C.), which must have been brutal and prolonged. The commander, Scipio, recognizing the strain under which his soldiers fought, took appropriate steps to protect them emotionally. In a long passage, Appian writes about the gruesome hand-to-hand warfare of street fighting. “Six days and nights were consumed in this kind of fighting, the soldiers being changed so that they might not be worn out with toil, slaughter, want of sleep, and these horrid sights” (Punic Wars, 130).

In 1868 Poynter produced another of his most celebrated Roman spectaculars, The Catapult. This shows Roman soldiers manning a siege engine for an attack on the walls of Carthage, during the siege which ended in the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC. The famous command of Cato the Elder, "Delenda est Carthago" (quoted in Pultarch's "Life of Cato") is carved in the wood of the huge catapult. The picture was a great success.

Plutarch

(Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.)

Life of Marius 45:

But Marius himself, now worn out with toils, deluged, as it were, with anxieties, and wearied, could not sustain his spirits, which shook within him as he again faced the overpowering thought of a new war, of fresh struggles, of terrors known by experience to be dreadful, and of utter weariness.

. . . Tortured by such reflections, and bringing into review his long wandering, his flights, and his perils, as he was driven over land and sea, he fell into a state of dreadful despair, and was a prey to nightly terrors and harassing dreams. . . . And since above all things he dreaded the sleepless nights, he gave himself up to drinking-bouts and drunkenness at unseasonable hours and in a manner unsuited to his years, trying thus to induce sleep as a way of escape from his anxious thoughts.

Lucretius (98–55 BC)

Lucretius wrote specifically about battle dreams, nightmares, and traumatic dreams in one of his philosophical works, De Natura Rerum,

Whatever employment has the strongest hold on our interest or has last filled our waking hours, to engage the mind’s attention, that is what seems most often to keep us occupied in dreams. . . . Generals lead their troops into action. Sailors continue their pitched battle with the winds.

Illustration of a seal bearing the head of Titus Lucretius Carus (about 94-55 BC), better known as just Lucretius. He was a Roman poet who is best known for his poem De Rerum Natura (The Nature of Things), which was written in six books.

Very similar to a rule is the behavior in the sleep of human minds, whose mighty machinations produce massive feats. Kings take cities by storm, are themselves taken captive, join in the battle and cry aloud as though their throats were being slit — and all without stirring from the spot.

A fragmentary inscription commemorated the life of the soldier Ulpius Optatus (CIL 8, 21562). It links ancient soldiers to combat stress. There are two halves of the inscription. The first half recalls Optatus’s bravery and mastery in fighting Rome’s enemies. The second part of the inscription interests them most. Optatus reached a point in the battle when his mind fractured somehow. The wording states, “as he unleashed his excessive anger in its entirety, that familiar rage of battle.” Many ancient and modern soldiers often reached hyper-arousal, or a ‘berserk’ state, suggesting P.T.S.D.

A.D.

Alderman Elfrick A.D. 1003

In the first millennium after the birth of Christ, in 1003, the English were battling the Danes. The English commander, Alderman Elfrick, apparently became violently ill so that he could no longer lead his men. His vomiting was perhaps the onset of P.T.S.D., in Part 3 of A.D. 920 -1014, “Online Medieval and Classical Library Release #17.”

14th Century A.D. Jean Froissart

Half-length portrait of Jean Froissart, historian, facing to the right. Engraved by Nicolas de Larmessin. Isaac Bullart. Académie Des Sciences Et Des Arts. - Amsterdam: Elzevier, 1682.

“Jean Froissart (1337?-1400/01) was the most representative chronicler of the Hundred Years’ War between England and France.” In 1388, Froissart lived at the court of Gaston Phoebus, Comte de Foix. He wrote of the case of the Comte’s brother, Pierre de Beam. Pierre would not sleep near his wife and children since he was in the habit of waking at night, taking hold of a “sword to fight oneiric enemies.”

Soldiers coming fully awake while having frightening dreams in which they reexperienced battles in their past is common in classical literature, as, “for instance, Mercutio’s account of Queen Mab in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet (I, iv):

Sometime she driveth o’er a soldier’s neck.

And then dreams he of cutting foreign throats.

Of breaches, ambuscadoes, Spanish blades,

Of healths five fathom deep; and then anon

Drums in his ear, at which he starts and wakes,

And being thus frighted, swears a prayer or two,

And sleeps again.

1666 The Great London Fire (see Illustration 12, p. 117)

According to Stephen Bentley, the Great London Fire of 1666 produced many P.T.S.D.-like symptoms in the population. It was a devastating conflagration that killed many and permanently brought deep suffering to the people of London. John Evelyn’s Journal of the Great London Fire of 1666 records the following:

'The Great Fire of London 1666'. The City is depicted on September 4th, the third day of the fire. Robert Hooke was in London at the time. Fortunately, the fire did not reach his rooms at Gresham College. Such terrifying destruction is on a par with the firestorms after World War II bombings. The narrow streets, timber-framed, thatched houses would later be replaced by brick, stone and tiled buildings to prevent such a tragedy happening again. Oil on board. Rita Greer 2008.

The conflagration was so universal, and the people so astonished, that from the beginning, I know not by what despondency or fate, but crying out and lamentation, running about like distracted creatures without at all attempting to save even their goods; such strange consternation there was among them.

Samuel Pepys personally described the fire in such terrible terms: “. . . and between churches and houses, as far as we could see up the hill of the City, in a most horrid malicious bloody flame, not like the fine flame of an ordinary fire.”. . . So great was our fear, . . . I . . . saw the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw; everywhere great fires, oyle-cellars, and brimstone, and other things burning. I became afeard to stay there long, and therefore down again as fast as I could, the fire being spread as far as I could see it; . . . how horridly the sky looks, all on a fire in the night, was enough to put us out of our wits; and, indeed, it was extremely dreadful, for it looks just as if it was at us; and the whole heaven on fire. . . . and there saw it all on fire, . . . and the fire with extraordinary vehemence. . . . and such fear of fire in my heart, that I took little rest.”

Two weeks later, Pepys wrote that he is “[M]uch terrified in the nights nowadays, with dreams of fire and falling down of houses.” The diary reports general feelings of anger and discontent over the next four months. Pepys then records that news of a chimney fire some distance away “put me into much fear and trouble. . . . At last [I] met my Lord Mayor in Cannon Street, like a man spent, with a [handkerchief] about his neck. To the King’s message, he cried, like a fainting woman, ‘Lord, what can I do? I am spent: people will not obey me. I have been pulling down houses, but the fire overtakes us faster than we can do it.’. . . So he left me, and I him, and walked home; seeing people all distracted, and no manner of means

used to quench the fire.”

1678 European Doctors

Stephen Bentley has done a massive amount of investigation on P.T.S.D. He tells us that as late as 1678, the Germans, French, and Spanish physicians had already identified the disorder we know today as P.T.S.D. They called it “nostalgia,” defining it by the empirical data, e.g., constant thinking of home, disturbed sleep or insomnia, weakness, loss of appetite, anxiety, cardiac palpitations, stupor, and fever. German doctors referred to P.T.S.D. as “Heimweh,” meaning “homesickness.” The French physicians, noting the same symptoms, called it “Maladie du pays,” and the Spanish termed it “estar roto,” or “to be broken.”

17th and 18th Centuries Doctor Josef Leopold Auenbrugger

In the 17th and 18th centuries, P.T.S.D., although not so named, was very much present during the never-ending wars once gunpowder became readily available. It was thought homesickness among the young troops contributed to the effects evidenced by the day's physicians. One such Austrian doctor, Josef Leopold Auenbrugger, noted P.T.S.D.-like symptoms in the closing days of the Seven Years' War.

August 1768 Capt. Jam

Mackowiak and Batten have done an interesting study on Capt. James Cook was the same Cook we all studied in school. Their article, “Post-Traumatic Stress Reactions,” discovered that from August 1768 to July 1771, Captain Cook’s maiden voyage, Cook recorded that the dangers he and his crew encountered were many:

Captain Cook's original voyages around the world, of his discoveries in geography, navigation, astronomy, &c., with memoirs of his life, and with memoirs of his life, and particulars relative to his unfortunate death.

Cook nearly perished when his ship struck a reef off Australia; he had his first encounter with cannibalism; he lost one-third of his men to a shipboard epidemic of unknown etiology, which also nearly killed him; and, after almost 3 years of the strains and stresses of command at sea, he returned to England to find that a son and daughter had died during his absence.

Not long after returning to England from his first voyage, Cook set about preparing another ship and crew for his second trip, lasting three years, from July 1772 to July 1775. It proved dangerous and demanding on the ship, crew, and especially on Capt. Cook himself. He set sail for Tahiti, sending him near Antarctica. Nearing Tahiti, his ship ran aground on a reef. The Capt. suffered from Gall stones, was wounded in the hand, witnessed cannibalism, and lost one of his Marines at sea. Cook returned to England, finished with the sea, and needed rest.

A year later, in 1776, Capt. Cook set sail on his third voyage against the better judgment of friends and seamen alike. Everyone who knew the captain appreciated him for his good humor, moderation, gentleness, and navigational skills. But something had changed about the captain. He became cruel, irritable, and profane as the ship’s skipper. Indecision invaded his decision-making. He vacillated as to his purpose and plans. Foolhardiness tempted him, as seen by his sailing at full speed into the fog when visibility was 100 yards or less. Against Hawaiian warriors, Cook was killed for no other reason than his provocation toward these islanders, choosing to fight rather than escape. P.T.S.D. Was this combat trauma?

The French and Indian War (a.k.a., The Seven Years War, 1756-1763)

Illustration depicting Braddock's defeat, performed by royal authority.

During the French and Indian War, Stephen Bentley’s research suggests “the symptoms (of P.T.S.D.) were believed to be associated with soldiers’ longing to return home and unrelated to actual battlefield experience.” In his “A Short History of P.T.S.D,” Stephen Bentley noted, “The French surgeon Larrey described the disorder as having three different stages. The first concerns heightened excitement and imagination; the second a period of fever and prominent gastrointestinal symptoms; and the final stage is one of frustration and depression.”

U.S. Revolutionary War (1775–1783)

The Continental Congress authorized one surgeon to serve in each regiment. Unfortunately, and all too often, regimental surgeons received their training through the apprenticeship system. There were only two medical schools in the United States (King’s College [now Columbia University] in New York, NY, and the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, PA). None had any experience treating trauma. The organization was minimal. Moreover, regimental surgeons tended to work for their unit instead of seeing themselves as part of the Hospital Department. Bureaucratic infighting rendered this system ineffective.

Revolutionary War (montage).

As early as 1685 in Philadelphia, the Quaker Society of Friends, following an earlier British law, the English Poor Law of 1601, took responsibility for the poor. The churches and private organizations established assistance for those in need. In England, the local citizenry was to “provide certain maintenance through compulsory taxation when a family was unable to provide for a mentally ill member.” In America, this help included those soldiers whose lives would be radically altered by the country’s revolution against England. “Widows, orphans, and invalids received aid, but only if they could not rely on relatives, friends, or other parties deemed to have responsibility for them.”

Azel Woodworth

Azel Woodworth was only 15 years old when he served at the Battle of Groton Heights in 1781. After enlisting the previous year in Captain William Latham’s matross company, which assisted in loading, firing and sponging guns, Woodworth helped defend Fort Griswold from invading British troops — until a musket ball struck his neck, just under his right ear, and exited along his spine, cutting through skin, muscles, tendons and bone. As Woodworth later recalled, the injury rendered him “insensible” for a “short interval.” Then, he “partially recovered” and resumed military action. The following day, however, his mental “faculties retired” and “returned not for 24 hours.” Woodworth’s wound not only caused his head to permanently rest on his left shoulder, but also significant intellectual incapacity that waxed and waned over the course of his life.

Woodworth’s injuries to his head, neck and intellect dramatically altered the adulthood he had imagined for himself at the age of 15. As he later wrote in a memoir — which was reprinted in William Wallis Harris’s The Battle of Groton Heights: A Collection of Narratives, published in 1870 — due to Woodworth’s “deranged state,” his father stopped teaching him a trade, believing that he would be “unable to progress in the study.” Even manual day labor, which Woodworth pursued as a result, “exhausted” his “mental faculties,” causing him pain and requiring frequent breaks. In the 1790s, the veteran married, had two children, and pursued a business in husbandry. Yet his difficulties in laboring soon led to financial troubles. Despite receiving a small monthly “invalid” pension of $1.66 from the newly formed federal government in 1794, by 1807 Woodworth had become a self-described “wandering person” dependent on the “charity of fortuitous friends.”

Richard Watrous

After Richard Watrous, a private in the Sixth Connecticut Regiment, was wounded in the Battle of Norwalk in 1779, he received intensive and prolonged support from fellow soldiers, doctors, family members and townspeople. Watrous was injured in his arms and torso by musket balls and bayonets, causing fractures and wounds, as well as disturbances to his mental state. As neighbors explained, he “appears to be lost & bewildered” much of the time, perhaps owing to “some radical injury to his constitution.” Watrous was first cared for by servicemen and former neighbors, then by physicians and military officers, and finally by family and community members at home. As one neighbor recalled, an officer “assured me [that Watrous] Should have all Possible Care taken of him,” a support that eased the veteran’s mental and corporeal struggles until his death in 1799.

The War of 1812

Gen. William Hull

The War of 1812 created more mental anguish for those involved directly. Symptoms of P.T.S.D. surfaced following the American Revolution. During the War of 1812, these traits were especially poignant in the life of Gen. William Hull. George Washington had seen Hull’s promotion to General for bravery during the War of Independence just before the Northwest Army’s devastating defeat at the Battle of Detroit. Gen. Hull was tried and convicted of cowardice, but President Madison commuted his sentence.

Gen. William Hull. Artist: James Sharples Sr. (1751-1811).

Hull, the hero of Saratoga and Monmouth’s battles, probably suffered P.T.S.D. to a much higher degree than was reported until the battle of Detroit. According to Joseph R. Miller, in “War and Trauma: The Dual Life of William Hull,” Hull’s daughter wrote of her father’s heroics:

It is sufficient for my purpose on this occasion, to notice particularly the capture of Burgoyne (Saratoga), and the well-known battle of Monmouth. In these two memorable events, where the ground was covered with the dead bodies of the slain, and the air resounded with the groans of the dying, Hull was unshaken. He bravely fought, and a grateful country acknowledged his bravery . . . . Having associated with him in times so interesting, and in no other character than that of a brave man, I shall be unhappy to learn that he has terminated his patriotic career by meanly acting the coward.

Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870)

Charles Dickens noted the symptoms he experienced after a train crash where ten people died and hurt as many as 49. He wrote, “I am curiously weak. . . I begin to feel it more in my head. . . but I write half a dozen notes, and turn faint and ‘‘sick’’. . . driving into Rochester yesterday I felt more shaken ‘‘than I have since the accident.’’ ‘‘I cannot bear railway traveling yet.” Charles Dickens wrote A Tale of Two Cities, which (published in 1859) can be considered as an early case report of PTSD" (Huber and te Wildt, 2005).

French neurologist Pierre Janet (1859–1947) (see Illustration 19, p. 119)

The French neurologist Pierre Janet (1859–1947) was one of the first scientists to empirically explore trauma’s psychological impact. In a study of more than 5000 patients, he suggested that traumatic memories have the ‘all or none’ feature. He also concluded that trauma is often decontextualized and misplaced in its historical context.

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0.

Janet recognized what he called ‘premeditation,’ when a person experienced a traumatic event and when the patient developed trauma-related symptoms. If the victim re-experienced a particularly traumatic event, Janet called this a dissociative flashback. Patients were incapable of processing the memories of a traumatic event.

Janet describes the concept of

‘misere psychologique,’ a degrading of the psychic functioning particularly observable in the wake of emotionally draining traumatic experiences.

1884

German physician Hermann Oppenheim first coined the term “traumatic neurosis.” Oppenheim described 42 cases of “railway or workplace accidents.” Charcot would have none of it. He insisted that “these cases were only forms of hysteria, neurasthenia, or hystero-neurasthenia.”

But after Charcot died, the French psychiatry adopted the term “traumatic neurosis.” The Belgian Jean Crocq reported 28 cases of railroad crashes, men and women who suffered from this neurosis. Symptoms included “dissociation caused by trauma, the pathogenic role of forgotten memories, and ‘cathartic’ treatment.”

Emily Dickinson December 10, 1830 - May 15, 1886

Emily Dickinson spent her entire life in Amherst, Massachusetts, sheltered from the outside world among her socially prominent family. As a child, she was “one of the wittiest girls in [her] school, a self-proclaimed free spirit,” and by the time she reached her middle teens, she was brimming with self-confidence, exclaiming, “I am growing handsome very fast indeed! I expect I shall be the belle of Amherst when I reach my 17th year. I don’t doubt that I shall have perfect crowds of admirers at that age.”

At the tender age of 14, four of her closest companions died unexpectedly, one following the other. Emily had little choice but to attend each funeral. “One of these deaths was that of a cousin of the same age, Sophia Holland, into whose room Dickinson stole moments after the girl died.” In her great distress, she could but stare into her late cousin’s peaceful face, transfixed, “until others pulled her away.” Simultaneously, Emily experienced a fever and then a cough that produced blood. This sickness continued for decades, so when she was 17, she quietly canceled her classes and resigned as a student at Mount Holyoke College. Miss Dickenson’s family had suffered from this disorder, and therefore, it was supposed to be hereditary.

Even though she became her mother’s primary caregiver, Dickinson secluded herself from almost all social contact by the late 1850s. She no longer wished to gather with close friends. Her church attendance waned and then became nonexistent. When guests approached, Emily would beat a hasty retreat. She developed an odd method of tolerating visitors. She agreed to converse with guests only at moonlight and then at her home’s back stairs. All her conversations came from behind a door or screen. Her doctor was allowed to examine her oddly. He would seat himself at the far end of the room, and as she walked by the open, he must make his prognosis. By age 35, her recovery seemed more assured. It was then she ventured outward into her social surroundings. At this time, her poems and essays began to blossom, and she became the writer we know today. “She died at age 56, most likely of hypertension complicated by a massive stroke.”

The Crimean War October 1853 - February 1856

During this war, “Irritable Heart” had been recorded, resulting in the incapacitation of soldiers. Light duty and rest were prescribed. “Many years after the end of the Crimean War, traumatized veterans are recognized as suffering from Da Costa syndrome or Effort syndrome, although neither name is used until long after the war.”

"Print shows soldiers transporting winter clothing, lumber for huts, and other supplies through a snow-covered landscape, with partially buried dead horses along the roadside, to the British camps; huts under construction in the background." tinted lithograph, digitized from the original print. Simpson, William, 1823-1899, artist., Paul & Dominic Colnaghi & Co., publishers.

The Attack on the Malakoff by w:William Simpson. Print shows the French assault on the Malakoff, the main Russian fortification before Sevastopolʹ, on 7 September 1855. French soldiers advance from the left, Zouaves from the left foreground, crossing the ditch and engaging. 23. The Crimean War Russian soldiers in hand-to-hand combat on the right. This was published on 22 October 1855, less than two months after the battle, which is about as contemporary to the event as mass-reproduced colour images got at the time.

The horrific suffering endured by the British troops in the Crimean War lacked the dignity and bat- battlefield honor afforded by Lord Tennyson’s poetic stoicism in “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” For of the approximately 20,000 British troops that died in the East, in a vain attempt to settle the “Eastern Question” of what was to become of the Ottoman Empire, only 10 percent were killed in action. Although thousands of Germans, Swiss, and Italians fought for the British Army, most of the British military was composed of fellow compatriots. However, death was no respecter of persons as the vast majority of British military casualties unceremoniously and needlessly succumbed to a varietyof factors afar from the battlefields.

Britain went to war ill-prepared medically or administratively. Army Medical Department Director-General Andrew Smith and his staff had no experience at war or preparing for it. However, by the conclusion of hostilities, Smith had published a beneficial work titled Medico-Chirurgical History of the War. The British Department of War Office published Smith’s work. The first volume was the “Precis,” which the War Office divided into two parts. The War Office further divided the second volume. This book, Medical and Surgical History of the British Army, which Served in Turkey and the Crimea during the War Against Russia in the Years 1854-55-56, became an essential part of British medical treatment. “(W)hen taken in its totality, the value of the publication is undeniable and provides insight into the overall health of the British military and the spectrum of maladies troops endured during the Crimean War.”

For of the approximately 20,000 British troops that died in the East, in a vain attempt to settle the “Eastern Question” of what was to become of the Ottoman Empire, only 10 percent were killed in action.

Of the “34,318 troops were deployed in the Crimea,” by June 3, 1855, roughly 48,039 served in Crimea. “By the end of March of 1856, and the Treaty of Paris signing, 111,313 British officers and soldiers had made it to the theater.” Statistics revealed “2,755 were killed in action and 2,019 died of wounds.” Officially, though, “the British government recorded a total of 21,097 deaths in the Crimean; thus 16,323 died of diseases.”

“It is difficult to recognise in their haggard faces and ragged clothing the gay soldiers who left us the other day. Every general and staff officer in our division was killed or wounded. The people who are left appear dazed and stupefied and unable to give us any idea of our position or chances.” -Lieutenant Llewellyn.

Long after hostilities ended in Crimea, “traumatized veterans are recognized as suffering from Da Costa syndrome or Effort syndrome, although neither name is used until long after the war.”

Florence Nightingale (1820–1910)

Florence Nightingale was a remarkable and religious woman, born into an aristocratic British family. Her parents educated her at home. Although frail, Florence was exceptionally independent and thoughtful. She grew into womanhood when British women had few rights, and the society passed over females of insight and intellect like Florence.

Nightingale had the courage and conviction to challenge her society’s strictures and take up the then-masculine vocation of nursing. In 1854, in her middle thirties, she traveled to Skutari (now Uskudar), Turkey, to care for British soldiers fighting the Russians in the Crimea. With a mere 38 nurses under her, she provided medical care to a seemingly endless stream of troops wracked by frostbite, gangrene, dysentery, and other diseases and crammed into 4 miles of beds not 18 inches apart.

Days came in endless cycles, seeing her nurse patients up to “20 hours a day.” Florence “took the most severe cases herself.” The following May, Florence was diagnosed with what was most likely brucellosis, a near-fatal illness. Weak and sick as she was, Nightingale refused evacuation back to England.

Nightingale’s work brought the field of public health to national attention. She was one of the first in Europe to grasp the principles of the new science of statistics and to apply them to military—and later civilian—hospitals. 1907 she was the first woman to be awarded the Order of Merit. Nightingale’s image has often been sentimentalized as the epitome of femininity, but she is especially remarkable for her intelligence, determination, and amazing capacity for work.

She remained with the Army during her convalescence and did not leave her post until the last soldier had left for home 21 months after her arrival.” Her nursing in such Spartan conditions, living among the dead and dying had hardened her, and she was visibly aged by her serious illness and resulting exhaustion. Intermittent fevers, anorexia, fatigue, insomnia, irritability, depression, sciatica, dyspnea, and palpitations dogged her for the next thirty years. Miss Nightingale seldom left her sofa and confined herself to her room.

Her memories haunted Florence of those who died after she attempted to nurse them. She was a “bereaved, haunted woman” who walked her room during the night, unable to sleep. It was not until into her sixties that her troubles began to subside. She had become a “cold, obsessed, and tyrannical workaholic.” Her more positive transformation came late in life, albeit gradually. The mental hardness produced by her medical activities during the Crimean War had softened, and Florence showed hopeful signs of life. She even began pursuing more normal relations with old friends. After attending to her last patient, Scutari had long since eroded the nursing desire. Miss Nightingale died of “old age and heart failure” at age 90.

Suicides

Director-General Andrew Smith cataloged “suicides” as death by “disease.” Eighteen “diseased” soldiers officially took their own lives. “Attempting to calculate an accurate annual suicide rate per 100,000 is impossible because it is unclear how many of the 111,313 military personnel arrived in-country for the basic two years of the war, but the range is conservatively between 8 and 16 per 100,000, with the likely answer somewhere near the middle.” Interesting is the fact that of these 18 suicides, all but two suicides served in different regiments. Medical staff documented fifteen of the 18 suicides as “Died in General Hospitals and elsewhere (not in Regimental Hospitals) during the War.”

The American Civil War 1860 - 1865

Death of General Thomas Williams at the Battle of Baton Rouge, illustration by Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War, Volume 2.

The first understanding that a traumatic event could cause psychological as well as physical injury. People traumatized by accidents on railways were referred to as having Railroad Spinal Syndrome by the English surgeon Frederick Erichsen.

Before the Civil War, there were no national cemeteries and no governmental procedure for even identifying the bodies of men lost in battle, much less for burying them. The nation had no “bureaucracy” of death simply because there had been no need for it. At first, most people saw the war as a minor contretemps or dispute. At the capture of Ft. Sumter in April 1861, no one expected it to last very long. Between April 12, 1861, and June 30, 1861, both sides suffered 30 casualties: four Union and 26 Confederate.

It is essential to understand how Americans looked at death before the war since that view is so alien to many of us now. Of course, death is always a part of life. The prevailing belief about death in the early decades of the republic was that the subject itself had become a prominent feature of the country’s mental landscape. This philosophy of death guided a person’s life. An omnipresent goal of having a “good death” meant dying at home. The departed had uttered his or her last words surrounded by loved ones.

Illustration by Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War, Volume 2.

During the war, a soldier wounded in battle, far from home, and about to die would often arrange photographs of family members around him. In this way, the soldier attempted a rudimentary battlefield version of the once-idealized good death at home. After June 30, 1861, this “good death” changed radically. During the Civil War, identifying the dead proved distressing to the men’s units and the family members waiting at home for some word from their relatives fighting in the war. In part, that was because of crude battlefield burials, if there were burials at all. The contempt each side eventually had for the other’s death was the cause. At Antietam, northern soldiers dumped 58 dead rebels into a well.

For the first time in modern history, war technology has outstripped man’s ability to cope. Men had raced headlong into their enemy’s ranks for millennia, facing spears and arrows. In the Civil War, the combatants faced repeating rifles and Gatling guns, delayed fuse artillery rounds that burst in mid-air, killing tens of hundreds of soldiers before they could get close enough to close with the enemy. No generation had faced telescopic sights and rifled bores that could reach out and strike men dead hundreds of yards away. The soldier did not have to participate in the battle to face exposure from a sniper too far away to see.

From 15% to 20% of the Union Army soldiers enlisted as volunteers between 9 and 17. Ninety-three percent of the men would likely “experience mental and physical disease.” Soldiers and POWs alike fell victim to “cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal symptoms, and would probably die “early.” Beyond the death and destruction of the war itself, many in the Union Army had relatives in the Rebel Army. “Family members” participated in trying to kill each other in close-quarter, hand-to-hand combat, with devastating consequences. This type of warfare caused tremendous distress not only because of the physical carnage but also because killing one’s kin at close range presented mental psychosis.

Daniel Folsom

Daniel Folsom, a tinsmith from northern New York, enlisted in the Union Army just days after the fall of Fort Sumter. His exemplary service through years of long marches and hard battles led to two promotions, but something changed during the Battle of Fredericksburg in late 1862. Folsom seemed un-easy. He was still troubled months later when the regiment mustered out. He returned home, opened his tin shop, and tried to focus on work.

As time passed, Folsom’s motivation to work waned. He neglected the tin shop and wandered aimlessly around the village. Folsom snapped in July 1863 when the draft called the first men in his neighborhood. Terrified that he would be sent back to the Army, he became sleepless and manic and then fell into a severe depression. When he attempted suicide, his family had him committed to the State Lunatic Asylum in Utica. In the asylum, the young veteran grappled with his paranoia and guilt. At times, he begged the attendants to kill him.

Folsom slowly began to improve. “I am not injoying myself much at present,” he wrote to his sister in the spring of 1864. Still, he assured her he had recovered and implored her to persuade their father to retrieve him from the asylum. Folsom was especially concerned about finding work. It seemed to him that the longer he was institutionalized, the less likely it would be for him to succeed in business. “I should like to get out of this city [and] go into business if I stay here any longer the world will be a blank,” he wrote. “I think there is a chance for me yet."

Wallace Woodford - Once back in the safety of his bed, “Wallace Woodford flailed in his sleep, dreaming that he was still searching for food at Andersonville. He perished at age 22, and his family buried him beneath a headstone that reads: ‘8 months a sufferer in Rebel prison; He came home to die.’”

Those soldiers diagnosed as “insane” from the exposure and rigors of battle would often wander about the countryside. Some died utterly unaware of the new dangers they faced. Many of these once brave but later broken men existed for years afterward and eventually committed suicide. Others spent their final days in insane asylums. Unfortunately, the government did little to maintain the hospital they had built for the Insane in 1863. Soldiers’ homes sprang up throughout the nation after the war, their need growing with the ensuing years rather than decreasing.

On November 11, 2014, HBO aired a documentary titled Wartorn 1861-2010, a film about combat trauma from the Civil War to Iraq and Afghanistan’s current involvement. Directors Jon Alpert and Ellen Goosenberg Kent found it difficult to locate and document information on Civil War veterans and their combat stress claims. Legal pension files recorded the families of the veteran’s descriptions of their loved ones who had returned home mentally altered. Often, the breadwinner could no longer function psychologically. From those files, individual tales revealed what the war had done to these men.

Brigadier General Philip St. George Cocke - Writing for the New York Times, Sommerville records. the suicide of the highest-ranking Confederate officer, Brigadier General Philip St. George Cocke. Due to losing his command and rank as the “appointed commander of Virginia’s state forces” once the war started, his superiors demoted him to Colonel. However, he regained his Brigadier General’s rank at the first battle of Bull Run, but his brain had suffered irreparable damage.

He commanded troops in the Battle of Blackburn's Ford and the First Battle of Bull Run

(First Manassas) in July 1861.

Psychologically and physically, these “perceived slights, on top of the strain of war, combined to take a huge toll on Cocke’s psychological and physical health. He retreated to his plantation a broken man, and on the day after Christmas 1861, he shot himself in the head with a pistol.” (see Illustrations 27, p. 122)

Suicide Rates During and After the Civil War

Hadley-Cousins gives some rather disturbing statistics from an official report by “The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion.” Eight hundred fifty-three soldiers were discharged for insanity, 1% of the total post-war discharges. That number is probably relatively low, considering the number of battles, the casualties, and the types of wounds sustained from five years of war. We are only made aware of the mental instabilities from the remaining asylum records. For men like Daniel Folsom, who believed he “still had a chance” and “I shall try and be a man,” as he wrote home later, reenlisting in the army helped “to reaffirm his manhood through battle.” Folsom survived the war as a 1st Lieutenant with a New York regiment, living to marry and produce six daughters.

Dr. Jacob Mendez Da Costa - Following the U.S. Civil War, doctors began to notice an increase in troops’ heart problems, attributed to fatigue from war conditions. Doctors treated fatigue, anxiety, high blood pressure, and irritable heart conditions with rest.

Sketch for Portrait of Dr. Jacob Mendez da Costa by Thomas Eakins.

In 1871, Dr. Jacob Mendez Da Costa converted the term “nostalgia” to “soldiers' heart” after noticing increased heart problems among soldiers and civilians. He attributed the symptoms to fatigue caused by excessive marching, complex service in the field, and missing loved ones. The recommended treatment for soldiers’ heart also consisted of rest. “Instances of sudden paralysis or loss of sensation were identified as traumatic hysterical neurosis.”

In 1981, M. R. Trimble reviewed case studies of railway accident survivors of the 1700s. These produced head injuries that Trimble traced. There appeared to be biological components that created PTSD-like symptoms. These indications gave rise to the term “postconcussion syndrome.”

According to Trimble, the English surgeon Erichsen attributed conspicuous psychological abnormalities following railway accidents to microtraumas of the spinal cord, which led to the concept of the “railroad spine syndrome.” This original connection drawn by Erichsen was later contradicted by the surgeon Page (1885), who objected to the phrase “concussion of the spine.”

Page believed that injuries to the spinal cord could produce emotions such as fright, fear, and alarm, contributing to the disorder. He suggested terms more aligned with the responses, e.g., “nerve shock” and “functional disorders.” Although Page argued that nervous shock is more psychological in nature and origin, the nervous system’s physiologic malfunction often results. In 1883, Putnam maintained that many of these cases, known as railroad spine syndrome, should better be associated with hysterical neuroses. Hermann Oppenheim first spoke of trauma and traumatic neurosis, a disorder he located in the cerebrum. Until that time, it referred almost exclusively to surgery. Suddenly, trauma could also deal with psychiatry.

The available data, then, scanty at best, would not support the assumed pathology of the spinal cord or heart disease. The question arose as to the interpretation of trauma for post-traumatic syndromes. External factors deduced from psychoanalytic understanding were quickly adopted as having significant weight in diagnosis. (see Illustrations 28, p. 122)

The History of P.T.S.D.: Post Civil War to WWII

Post Civil War

W. C. MacLean conducted an 1865 study at the Army Medical School in Netley, England. MacLean based his report on a previous Crimean War investigation by de Costa on soldiers’ equipment. The study suggested the equipment needed a redesign. The government issued rucksacks and waist belts that ‘were thought to restrict circulation through the heart, lungs, and great vessels.’ In well-disciplined regiments, the practice of falling out at drill or on the line of march is discouraged, and [that] men will bear and suffer much, rather than incur the imputation of being ‘soft.’”

In 1871, Jacob Mendez Da Costa published a study on “irritable heart.” Determined military doctors attempted to isolate the growing caseload of “heart disorders” that there “was actually an organic response to battle stress.” In 1873, the U.S. Congress passed the Consolidation Act, rating disabilities for various levels of impairment during the Civil War, according to Blanck and the Bradley Commission of 1956. If a veteran could prove that his disability was caused by his military service, even though such action originated from combat, his present disability was deemed pensionable. Unfortunately, corruption in the disability process increased until the print media published stories verifying “exaggerated and faked claims of disability.”

De Costa reported in 1919 that 38.5% of his 200 psychological disorder patients endured “hard field service and excessive marching.” This meant, according to Meager, they lived under constant threat of death or dismemberment. In that same report, 30.5 % had bouts with diarrhea.

Eighteen eighty-eight brought a Commission of Pensions report to Congress detailing its findings. From 1862 through mid-1888, revealed that a greater number of awards were granted for delayed-onset diseases than for service-incurred injuries. Among the Commission’s reported statistics were 5,320 pensions for nervous prostration and 1,098 pensions for “disease of the brain, including insanity.” An astounding 25,994 cases of “diseases of the heart” were reported.

The Boer War October 11, 1899 – May 31, 1902

Doctors diagnosed and documented functional disorders during the Boer War, making the death certificates more understandable but not necessarily more accurate. Traumatic stress death certificates read, “Disordered action of the heart” or “valvular diseases of the heart.” “The South African War (1899–1902), for example, saw large numbers of British servicemen discharged from the armed forces with a diagnosis of disordered action of the heart (DAH), thought to be the effect of exertion on a soldier’s chest constricted by tight webbing and equipment.” Some soldiers showed symptoms that resembled Gulf War Syndrome. A civil surgeon, Anthony Bowlby (1855–1929), worked at the Portland Hospital in Rondebosch and Bloemfontein in 1900. Bowlby recalled the symptoms he saw in his patients, which included “pain, in the form of headache, generally posterior, pains in the neck, pains in the back and limbs so that these cases are generally sent back as cases of rheumatism; general feebleness of the muscular system amounting to paralysis more or less pronounced.” Seventy-seven percent of British soldiers saw action during this conflict instead of 19% of Gulf War soldiers.

Clockwise from left:

Boers in action at the Battle of Colenso, the 17th Lancers holding of an attack at Modderfontein, General Redvers Buller entering Ladysmith on 27 Feb 1900, Boers at the besieged city of Mafeking, Canadian Troops during the Battle of Paardeberg, and Boers before action at Spion Kop.

Troops who fought in the Boer War often had to march considerable distances to engage the enemy; it was a war of movement without mechanization. Contemporaries believed that the physical exertion involved was, in part, responsible for the various heart disorders encountered. Similarly, shell shock was framed in terms of trench warfare: an expression of the terror felt by men forced to endure the effects of artillery bombardment often without adequate protection and in identifiable positions. Fifty-nine per cent of wounds inflicted on British soldiers were as a result of artillery, and three times as many men were killed by shells as by bullets.

Australian civilian medical authorities during the late nineteenth century believed insanity as a sign of moral weakness. This view resulted “in a feminized view of mental illness.” Real men didn’t go insane because of combat. Therefore, these men had to be kept away from other hospitalized war veterans and sent to insane asylums. “Mental illness among men posed a threat to this legend (‘idealized masculinity’). The Australian colonies mythologized masculinity. The importance of nation-building and rural industry had amplified the masculine ideal, creating the ‘bush worker’ hero of the Australian outback.”

What created such consternation among physicians and Government officials in Australia and Britain was the caliber of men sent to fight in South Africa. New South Wales sent “thousands of unemployed ‘bush workers’ or rural workers.” Joblessness of these types of men meant, “These troops directly represented the ideal Australian male, but this hyper-masculine image precluded the possibility of psychiatric disorder, whether combat-related or not. The Australian concept of selfhood combined with colonial views of ‘insanity’ meant that military authorities questioned the possibility of combat-related psychological trauma. In other words, the concept of the ‘insane,’ feminized soldier was inconceivable.” Even by the time World War I was in full swing, doctors and Government officials had not linked psychiatry and combat.

Treatment: The Russo-Japanese War (1904-1906)

Japanese soldiers entering a bombed fort to find dead and wounded men. Halftone, c. 1905, after C. M. Sheldon, from photographs.

. . . Russian attempts to diagnose and treat battle shock represent the birth of military psychiatry. The Russians’ major contribution was their recognition of the principle of proximity, or forward treatment. Although it’s believed by most armies today that the Russians were right in treating psychiatric casualties close to the front, with the goal of returning them to the fight, the recorded rate of those who returned to battle suggests the method was not very successful. In actuality, less than 20 percent were able to return to the front.

Russian psychiatrists

The most notable Russian psychiatrist was Avtocratov, who first developed what came to be known as “forward psychiatric treatment.” Russian doctors and military command first noticed Post-battle neuro-sis. Avtocratov ran a 50-bed hospital for treating psychiatric patients at Harbin, Manchuria. The Trans- Siberian Railway was not yet completed, and moving psychiatric patients over rugged terrain and long distances created the need for close-to-the-front treatment. In 1904, doctors treated some 1500 patients. In 1905, that number increased to 2000, precipitating calling in Russia’s Red Cross Society. A German doctor, Honigman, served in this body. It was Honigman who labeled traumatic patients with “war neurosis” [Kriegsneurose] in 1907. Previously, psychosis was called “combat hysteria” and “combat neurasthenia.” Honigman also noticed a similarity between Russian war survivors, and Oppenheim’s re- ported railway crashes.

World War I

A German trench occupied by British Soldiers near the Albert-Bapaume road at Ovillers-la-Boisselle, July 1916 during the Battle of the Somme. The men are from A Company, of the 11th Battalion, The Cheshire Regiment.

By the outbreak of the First World War, doctors diagnosed actual psychiatric patients with weak character. Rather than continue to participate in or witness further wholesale disintegration and slaughter of entire armies in France’s muddy trenches, men often fled their posts. Many soldiers went into hiding. The French Government discovered them and subsequently shot them by firing squad for cowardice and desertion of duty. Of the 117,000 Americans killed, over 200,000 were wounded in action, and almost 160,000 had become psychiatric casualties. The military permanently discharged seventy thousand mental cases from the service.

Shell Shock

During World War I and World War II, psychological trauma was termed “shell shock” and considered to be the result of mortar rounds and artillery shells that continuously bombarded the troops. This phrase became the standard reference to traumatized troops. It was coined by Myers, a British military psychiatrist, in 1915.

Gallipoli 1915. The dead bodies of 36 members of the 11th Battalion Battalion killed during the capture of Leane's Trench.

“Has vivid dreams of war episodes—feels as if sinking down in bed”; “Sleeping well but walks in sleep: has never done this before: dreams of France”; “Insomnia with vivid dreams of fighting”; and “Dreams mainly of dead Germans...Got terribly guilty conscience over having killed Huns.”

Mott wrote a year after the Armistice, describing neurosis, hysteria, and neurasthenia as physical shock and horrifying conditions that could cause fear, which in turn produced an intense effect on the mind. Hysterical symptoms included paralysis, contractions, disordered gait, tremors, and shaking. Neurasthenia symptoms included lassitude (mental weariness), fatigue, weariness, headaches, and particularly vivid and terrifying dreams . . . startle reflex.

Probably over 250,000 men suffered from ‘shell shock’ as result of the First World War. The term was coined in 1915 by medical officer Charles Myers. At the time it was believed to result from a phys- ical injury to the nervous system during a heavy bombardment or shell attack, later it became evident that men who had not been exposed directly to such fire were just as traumatised. This was a new ill- ness that had never been seen before on this scale. The condition was poorly understood medically and psychologically. Take a look at the War Committee Report (WO 32/4748) on the condition to find out more about attitudes towards it just after the war. Today, the condition is known as post- traumatic stress disorder and the treatment and attitude to it are very different.

Neurasthenia

Shell-shocked soldier. Australian Dressing Station,Ypres, 1917. The soldier in the bottom left exhibits a typical sign of shell shock – "the thousand-yard stare."

Two cases of neurasthenia also give details of trench warfare and other injuries. The symptoms of this condition include physical and mental exhaustion with headaches or irritability, which can be linked to depression or emotional stress. Many ‘shell shock’ cases displayed symptoms of neurasthenia. (Catalogue ref: MH106/2101)

Neurasthenia is an ill-defined medical condition characterized by lassitude (mental weariness), fatigue, headache, and irritability, associated chiefly with emotional disturbance. In 1914, thirty-two year old Cpl. A. Xxxxxxxxxxx had served sixteen years in the British military. Xxxxxxxxxxx served with the First Cheshires when he suffered a traumatic injury in France. Captain B. McFarland recorded on September 12, 1914, the following about Cpl. Xxxxxxxx at 4th Northern General Hospital, Lincoln:

He has only four front teeth-top side two molars, bottom side and he could not eat biscuits.

On the 7th last month he was out scouting at 7.30 he got 1½ miles into enemies’ lines by mistake he was on a bicycle & had orders to retire- when ½ way back Germans opened fire on either side of road- this corporal was last man. They put a log in front of bicycle & threw him head over heels into a German trench & two of them took him prisoner to their quarters. At 2.30 their [position] was blown for an attack & the 2 … left him & whilst they were away, through a hole in the hedge behind his trench he scrambled to a barn & then jumping into German trench & ran up it for 100 yards until he saw the telegraph lines of British troops. He then ran across the road, jumped into a trench 2 feet deep and then there were about 50 shots fired at him, then he saw the Bedfords Regiment & reported position of enemy to them. He has been subject to Neurasthenia ever since. He was sent to 14 General Hospital for 4 days & then sent on here.

He is much better, sleeps well & eats well & no pains. He will be fit for furlough in a few days.

Six months later, L/Cpl. J. Xxxxxxx had served for thirteen years with the 2nd Lancs. Fusiliers and subsequently sent to 4th Northern General Hospital, Lincoln, from July 6-9, 1915, suffering what Capt. McFarland diagnosed as Neurasthenia.

On 5th May at Ypres he got a severe attack of Gas Asphyxia & was three hours unconscious, his nerves were bad after that, he had a bad shock in the end of November, a Jack Johnson [type of shell] fell about 10 yards from him. It killed 4 horses, wounded 3 men & killed a civilian. In February three shells fell on the house he was in & the roof fell in on top of him but he was not much hurt. He was sent to Etaples Hospital for 11 days. He was sent then to Rouen. Arrived here 18th June, Complaining of pain in head, his nerves are completely shattered. He has bad teeth they want attending to. Old caries [dental cavities] and decayed teeth want removing and a new plate ordered [dentures]. Rest.

Light diet and bromide mixture.

B. McFarland Captain R.A.M.C.

4th Northern General Hospital

Caught a feverish chill and referred to bed.

Temperature down to normal but still complains of pain in legs and given only milk diet still.

During the First World War, 306 British soldiers were executed for cowardice. “Herbert Morrison, . . . was the youngest soldier in the West India Regiment when he was led in front of the firing squad and gunned down for desertion. A ‘coward’ at just 17. . . . To this day, the Ministry of Defence refuses to give a pardon to the 306, convicted of cowardice, though even in 1914, people knew all about ‘shell shock’ - what the modern world calls Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. . . . The historic shaming of men - and, consequentially, their women and children - happened in other countries too. In France and Germany, men were shot for cowardice and desertion. But in the case of Germany, only 25, not 306. And in both countries, that shame was lifted within a decade of the war's end when official memorials were built.

“Only in Britain do we continue to dishonour the victims of shell shock. The Government’s argument

echoes the one first set out by John Major. He told the Commons that pardoning the ‘deserters’ would be

an insult to those who died honourably on the battlefield and that everyone was tried fairly.”

Military doctors, therefore, had to revise the “weak” or “cowardly” diagnosis. As the need for “volunteers” to fight increased, the gains made by Army doctors in treating mental health veterans were soon revised downward by a simple formula, “predisposition plus stress equals collapse.” In British medical studies during the war, what was known then as “post-emotional etiology” moved to the foreground. Post-concussional etiology (origins) receded somewhat, the latter being considered an honorable organ-ic etiology. Germany emphasized not wanting to return the patient to the battle. Therapy then was to isolate the soldier in a dark environment and then conduct shock treatments. Regardless of using these severe shock treatments, doctors returned patients to duty without being healed.

French soldiers sent to hospitals were often considered malingerers and, when released, were tracked down. One such soldier, Louis Ferdinand Destouches, alias Celine (1894-1961), tells his story in his Voyage au bout de la nuit (Journey to the Edge of Night). After several days of fighting, he recounts Ferdinand has a fit of madness while on leave. In the hospital, he tells the army medics that he has been driven mad by fear. He finds himself in the company of others, psychologically submitting to stringent medical monitoring. After a few days, doctors divided the patients into three categories: the first returned to the front, the second involved transferring these men to a psychiatric hospital, and a firing squad shot the malingerers. Sir Grafton E. Smith and T.H. Pear preferred “war strain” to “shell shock.” Incapacitation of one’s duties did not originate from the concussion of artillery rounds.

Second Lieutenant Bertwistle

. . . with two years of service in the 27th Australian Infantry, although only 20 years of age, whose face wears a “puzzled expression” and who exhibits a “marked defect of recent and remote memory.” “His mental content appears to be puerile. He is docile,” according to the records that accompanied him from the Royal Victoria Military Hospital in Netley, on England’s south coast.

Lieutenant Graves

Graves had gone straight from Gallipoli “into line & through Somme.” In fighting around Beaumont Hamel in France, a shell had landed “quite close & blew him up.” Dazed, he was helped to the company dugout, after which he “Managed to carry on for some days,” although an ominous “Weakness of R[ight] side was developing steadily.” Ironically, it was precisely the soldier’s ability “to carry on” that had aroused skepticism over the real nature of his malady.

Suicide Rates During and After WWI

The worst figures regarding WW I suicide rates happened in the years following the Great War. The causes were due to what we now know as “P.T.S.D.” Unfortunately, the suicide of combat veterans years after their service is still all too common today. One can only imagine how bad it was in W.W.I. Combat trauma had various labels then. It was known as “Shell Shock,” “Combat Stress,” or “War Neurosis.” Combatants diagnosed as such were typically labeled “cowards” or believed to be “lacking in moral fiber.”

The “lucky” were discharged and sent home untreated. Authorities hospitalized a minority of the “cowards.” The military made examples of the “unlucky” soldiers and gave them a “field court-martial.” The trial resembled more of a “Mock trial” or “Kangaroo court.” They were found guilty, sentenced to death, and shot by their comrades. “Knowing they would face such action, and the disgrace associated with such issues, suicide amongst front line soldiers soared.”

Canadian Suicides

Jonathan Scotland, writing about the suicide rate in Canada during the First World War, has noted, “Not a single study exists on Canadian suicide in the First World War.” However, Scotland does mention a few Canadian soldiers who served during that war.

On 20 January 1919 Charles Campbell killed himself. The resident of Brockville, Ontario was the first of many veterans of the First World War to commit suicide that year. Others included Ross Puttilo, Alexander Fowler, William Bailey, and William Dowier. There would be more. Their deaths remind us that recent suicides in the Canadian military are part of a longer historical trajectory of soldier suicide.

Scotland listed male suicides by Age/Military Service in the Toronto Globe and the Toronto Daily Star newspapers one year after reporting the Armistice signed in 1919. The Toronto Globe revealed that42 the total number of male civilian suicides was 57%, compared to 43% of the veteran population. From 1880 to 1900, all male suicides comprised 28% civilian and 72% veteran. The Daily Star, covering the exact statistics, found 69% civilian suicides to 31% veteran. From 1880 to 1900, 20% were civilians compared to 80% veteran suicide rates. This rate means that in 1919, about 40% of all reported suicides in Toronto, Canada were on the veteran side.

Moreover, if only the suicides of men aged 18-39 (those most likely to serve) are considered, then the percentage of reported veteran suicides doubles to nearly 80%. Clearly the suicides being reported in the press were disproportionately soldier suicides.

Economic difficulties encountered by Capt. William Dowler of the Canadian Medical Corps led to his suicide in November 1919. He refused, due to his pride, any financial aid. Often, the men mentioned above, and those not described, became “despondent.” Some had suffered tremendous wounds; others had not. Employment varied as well. “But one thing is clear: their suicides are invariably attributed to the war. Moreover, in The Globe and The Star, the reports show no sign of shock, shame, or surprise at this conclusion. Indeed, in almost every case, the war is widely accepted and unchallenged as the cause of their suicide.”

New Zealand and Australia

Compared to “Australia, Great Britain, and the United States—in wars since World War I,” the New Zealand soldiers “suicide rate is nearly twice as high as American World War I soldiers treated in V.A. hospitals in the 1920s, but identical to that observed by Minogue in his study of World War I veteran suicides in New South Wales.”

In New Zealand, statistics revealed that suicides among returning veterans from the Great War ranged from two to four times as high as men not having gone to the front. Queensland, Australia’s statistics are quite similar to those of Canada, post-war.

One unnamed blogger has written a dissertation about suicide in WWI. His purpose was phrased with a question mark, “Suicides in World War One?” He noted, for instance,

Unfortunately, suicide was quite widespread due to varying factors. It was especially a problem on front line areas where the worst horrors of WW I were known to occur. The more frequent cases were invariably on the British and French front lines, where soldiers in general could expect to remain on the front line for longer periods than their counterparts in the U.S. Army for example (after their entry), or even their enemy in the German trenches.

Desertion was an increasing problem from those suffering conditions such as “shell shock,” the usual penalty, a firing squad. Companies of French soldiers “mutinied" at points of the worst fighting, however, few were punished for doing so, unlike the British.

Whilst there are very few statistics on how many suicides there were exactly, soldiers suicided by varying means, usually their own weapon or grenade. Others simply went over the top of the trench they occupied knowing full well they’d be shot by the enemy, a phenomenon we know today as “Suicide by Proxy,” but nevertheless an act of suicide.

Britain

The Journal, a British newspaper, printed the May 28, 1915 headlines and article as follows,

SOLDIER AND HIS WIFE ASPHYXIATED.

REMARKABLE EVIDENCE AT THE INQUEST.

DID NOT WANT TO BE PARTED.

Under two pictures of the deceased printed in the Journal were published these final words,

Shadrach Critchley, 35, and his wife Annie, 45, were found lying side by side on a mattress at their home in Leigh, Greater Manchester, on Monday May 24 1915 - shortly after Mr Critchley was recruited to the army.

According to friend and fellow soldier Richard Adamson, he was at the Fleece Inn the night be-fore he was due to rejoin his regiment, telling him he had made a mistake in enlisting in the forces.

Mr Adamson said he had tried to reassure him it would be fine but when he went to the Critchleys’ house the following evening, he forced open the door and found both Shadrach and Annie on a mattress on the kitchen

floor.

An inquest heard the couple had written notes expressing their wish not to be parted, and were buried together in St Paul’s churchyard in Westleigh. At the inquest, the jury, who heard evidence concerning their deaths, recorded a verdict of temporary insanity.

Mr Critchley’s name was finally given posthumous recognition when he was placed on the Brookwood Memorial, in a list of around 500 men who died on British shores.

Gallipoli

Future British Major Guy Nightingale would survive the horrors of the Gallipoli campaign without a scratch. After the Gallipoli disaster, the British military transferred its unit to the Western Front in France. He left the service in 1926, and retired to Somerset but struggled to adjust to civilian life. He died by suicide in April 1935, the 30th anniversary of his landing at Gallipoli, having suffered from alcoholism and depression.

On April 18th, 1935, in the peaceful English village of Wedmore, in Somerset, at the quaint address of Thatch Cottage, Guy Nightingale died within a week of the 20th anniversary of his landing on V Beach. Three causes of death were listed on his death certificate: cardiac syncope, delirium tremens and chronic alcoholism. Some said Nightingale died by his own hand; a doctor now might simply at-tribute the ending of his life to post-traumatic stress disorder.

Irish Suicides

Since Ireland fought alongside British soldiers, we would expect suicide rates to be comparable for both British and Irish soldiers. What was discovered is quite interesting. “(D)using the 5 years of the First World War, there was a significant reduction in suicide rates for men by 18.9% (95% CI 3.7 to 24.2).” Male suicides declined. After the conclusion of hostilities, French suicides declined, although there was the potential for under-reporting deaths by suicide by local registrars. Émile “Durkheim’s so- cial theory of suicide indicated that Irish men may have focused on the collective goal of defending their island rather than their suicidal wishes during the 1914–1918 war.”

French Suicides

Painkillers, including aspirin which “they consumed in astonishing amounts,” according to Sliosberg, were heavily prescribed: pyrethane, nealgyl, sedatives, or vitamin B1 coupled with physiotherapy, radiotherapy or ionization. “These methods fail or even aggravate the situation,” explained the same author. The surgeon Leriche highlighted the use of morphine and its consequences: severe constipation (lasting eight to ten days) and addiction or dependence, with the alternative being sometimes suicide. Leriche wrote: “We must not let them become morphinomen: the amputee with an addiction to morphine is incurable. Sooner or later, he will reoffend. Believe me, I cared for forty of them.”

The war created new societies in France. The disfigured formed groups of men whose faces had been mutilated beyond recognition, known as the association “the broken faces” and l’Union des Blessés de la Face. This horror drove many disfigured men to suicide, although this self-inflicted death was rare. The doctors and staff didn’t mention suicides, but they knew it occurred.

Amputees gathered in their companies for support. Pain, unknown before the war, was their constant

companion. “(T)he wounded now belonged to a group of stigmatized men, their faces ravaged by war, seemingly inhuman.”

British Suicides

In 1916, a young British private in northern France wrote home to his parents explaining his decision. to take his own life. A survivor of the early days of the Somme, considered one of the most brutal battles of World War I, Robert Andrew Purvis apologised to his family before praising his commanding officers and offering the remainder of his possessions to his comrades. Purvis’s surviving suicide note remains one of the only documents of its kind from World War I.

The Most Famous American Suicide of the First World War

Col. Charles Whittlesey

Few of us today know the story of Col. Charles Whittlesey and the Lost Battalion. Their heroics are the stuff of legend. The Great War Society has compiled the following:

In Europe, Whittlesey served with the 77th Division, 308th Battalion, Headquarters Company. He was involved in defensive endeavors, first behind the British front and later in the Luneville Defensive Sector. Beginning in August 1918, Whittlesey’s Division entered real combat in the Vesle, Aisne, Argonne and Meuse offensives. Whittlesey gained world-wide recognition in October 1918 when the companies of his battalion, which were part of a campaign against the Germans in the Argonne Forest, were cut off for several days without adequate supplies of food or ammunition. Though it was often blamed on Whittlesey’s own overzealousness and inexperience, the troops of the 308th were left vulnerable to being surrounded by the enemy. Their own successful advance, and the inability of the Allied troops on the flanks of Whittlesey’s advance, had left them in such a position.

On October 2nd, when the companies of Whittlesey’s battalion and other units assigned to the 308th Infantry were first surrounded, they numbered 463 men. Parts of other units including some men of the 307th Infantry under the command of Nelson Holderman joined the main group bringing the total trapped to about 550. By October 7th, when Whittlesey’s troops were rescued, they had been reduced to 194, alive and unwounded. While the 308th Infantry was cut off in the “Pocket,” a hill between Charleveaux Brook and the old Roman road and railroad in that sector, they were subjected constantly to machine gun and trench mortar attacks by well-supplied German troops. In addition, the trapped men suffered from what is now called “friendly fire.” The runner chain from the ‘Pocket’ to Headquarters had been broken and the only means of communication was by use of homing pigeons. Unfortunately, one of the pigeons brought somewhat inaccurate coordinates back to headquarters. After much additional suffering, the last pigeon, Cher Ami, was used on October 4th to stop this friendly barrage. . . .

Early on October 7th, before the relieving Allied troops arrived, the German Commanding Officer who surrounded the Americans sent a letter to Whittlesey by an American prisoner requesting his battalion’s surrender. Whittlesey and George McMurtry, his second-in-command, refused to acknowledge this request and even pulled in the white panels used to signal Allied planes for fear the Germans would mistake them for surrender flags. It was widely reported in the American press that Whittlesey had responded “Go to Hell!” immediately upon reading the letter. He later denied having made the statement, suggesting that no reply was necessary.

The eventual relief occurred when several runners were able to break through the German lines to the south and lead the advancing troops to the ‘Pocket.’ Whittlesey was promoted from Major to Lieutenant Colonel upon the relief of his beleaguered troops. He was relieved from further duty on October 29th and returned to the United States. On December 5th, through the issue of Special Order No. 259 from Headquarters at Fort Dix, NJ, he was honorably discharged from the United States Army. The following day, December 6th, he was named a recipient of the Medal of Honor, the highest award given by the U.S. Army. His subordinates, Capts. McMurtry and Holderman would also be awarded Medals of Honor for their service in the pocket. . . .”

Congressional Medal of Honor Society reported the following: